Spaced Repetition: My Learning Secret

There are people who can study the night before a test and ace it. I am not one of those people.

Although I loved school, I was really bad at studying. In fact, I hated studying. I studied by reading my notes and the textbook, trying to make sure I understood the “fundamentals” and “core concepts”. Of course, I did this in the days or hours leading up to a test. Even when I started to study earlier, I found I needed to go back over content I already thought I had “learned”. Studying was boring, discouraging, and ineffective.

During university I stumbled upon a technique that allows me to learn and retain information extremely well — spaced repetition.

Spaced Repetition

The gist is you make a set of flashcards using software and practice them every day. Every time you review a card, you can tell the program if you knew the answer and how easily you recalled it.

Now, that’s easier said then done. This technique is not a shortcut to learning by any measure. Learning using spaced repetition takes a lot of time and effort. You must review your cards every day.

We all know that over time our memory for facts decays. It turns out that if we cause our mind to recall a fact right before we are about to forget it, we will strengthen the memory. In more concrete terms, if we learn a fact, recall it in increasing intervals of say 10 minutes, 1 day, 3 days, 5 days and so on we will be able to remember it for much longer. For a better overview of the science, checkout this Wikipedia article.

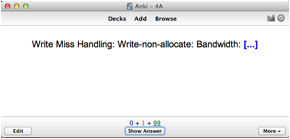

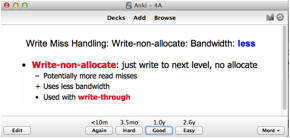

Spaced Repetition Software manages this for us. Here’s an example of one of my cards from a Computer Architecture course:

Note the time on this card is a little extreme because I haven’t reviewed this card in over a year. You can see that I provide a lot of context on my cards. I also included an excerpt of the lecture slide. I’ll talk more about constructing good cards in a bit.

Learning or Memorizing

When I’ve told friends about the technique, they are skeptical that I actually learn anything and posit that I am just blindly memorizing. I too initially thought flashcards were only for pure memorization.

I initially tried spaced repetition originally because a lot of concept heavy courses still had facts or rules that I frequently forgot. During an exam I would know what the question was asking, how to answer the question and even most of the facts or rules. However most is not all.

As I used spaced repetition more often, I found myself adding cards to “memorize” the relationship between concepts or ideas. For example I had a card to differentiate between conflict cache misses (a miss caused because the cache associativity is too low) and coherence misses (a miss caused because some external force invalidated a cache line, like in a SMP).

At first glance this appears like I’m memorizing the differences between the two concepts. In some sense I am, but if I can correctly contrast between the two misses have I not learned the concept? Even more interesting is that with this knowledge I can actually understand the implications in the real world.

After a while, I learned to create flashcards that required really understanding the material if I was to answer the questions correctly. This is when I started to see the benefit. Trying to memorize a card without understanding it can work for the short term, but after longer intervals I found recalling facts extremely difficult.

Creating Cards

I use Anki for my spaced repetition. It’s free for desktop and can sync with your mobile devices.

I skip class and instead sit in front of my large monitor with the lecture slides on one side of my screen and Anki’s card editor on the other. I read the slide (and surrounding slides) to determine what the concepts are. I create cards that cover these concepts from multiple angles. When in doubt I add more concepts than less.

The authors of another spaced repetition software, SuperMemo, has an excellent set of rules for creating cards called “The 20 rules of formulating knowledge in learning.” I’ll outline the rules I felt particularly helpful here.

4: Stick to the minimum information principle

It’s easier to learn small and concise pieces of information.

5: Cloze deletion is awesome

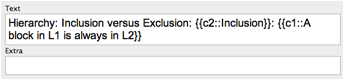

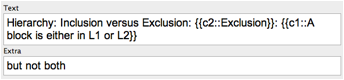

Almost all of my cards use Cloze deletion. It’s much more effective than standard flashcard with a front and back. You can use the cloze deletion for multiple parts of a concept. This allows you to recall the concept from different sides.

6 and 8: Use Images (and image cloze deletion)

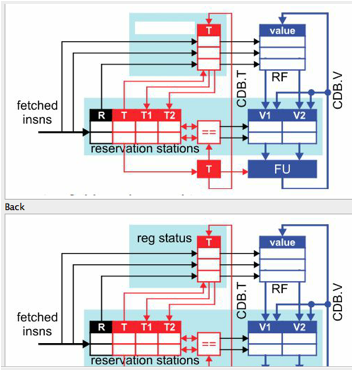

Here’s an example of a Tomasulo’s CPU register renaming technique with a visual cloze deletion. Notice how the only the only item removed is the register status. That’s the level of detail that I found useful. I use the Anki plugin Image Occlusion to create image cloze deletions quickly.

9 and 10: Avoid Sets and Enumerations

Remembering sets and enumerations (ordered lists) is unnecessarily difficult. You can often convert these into more meaningful and useful cards. Usually I do this by contrasting and comparing concepts as in the inclusions versus exclusion cards earlier.

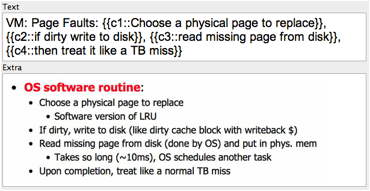

If you can’t find a better way to represent the concepts, cloze deletion on a list can really help out. This card describes what happens during a page fault. Every time I review the card I see all but one step, allowing me to think about the step in the context of the other steps.

11 and 16: Combat Interference

Interference is when two cards are similar and you confuse the concept and therefore the answer. Inference is extremely frustrating, especially if the two cards are separated by time.

Consider two similar concepts far apart from each other in the deck. You may learn the first concept perfectly. Later the second concept is hard to learn but you eventually figure it out. As time goes on the first concept comes up again and you’ve forgotten about it.

One of the ways I deal with interference is by providing lots of context in the card to differentiate concepts as in the cache hierarchy example. I sometimes go back to cards and modify them to be dissimilar.

12: Omit needless words

If you cards contain a lot of unnecessary words, you brain takes longer to make the connection to the concept. I tend to write verbosely so I actively try to limit the amount of wording on a card, eschewing grammar.

17: Redundancy is OK

I often have several cards that cover the same concepts from different angles. Sometimes using cloze deletions, images, or comparisons to similar concepts. These all can help strength memories. Approaching a concept from different angles also ensures you can recall the concepts in different situations.

A Topological Sort of Knowledge

A theory on learning I once heard was that in order to learn a concept you need to have a hook to hang it on. In other words, you need to see where an idea fits in the bigger picture before you can internalize it.

One way to do this for lectures is to pre-read lecture slides. That way when the professor is presenting the information, you’ll already know where it fits. I did this for my Data Structures and Algorithms class before I used flashcards and it was a boon for my understanding and my exam mark.

Ideally, we would be presented with information in the perfect order for learning, a topological sort of knowledge so to speak. However, it’s difficult (perhaps impossible) to construct a perfect ordering. Spaced repetition allows us to approximate this idea.

When you are reviewing cards, they will not necessarily be in the order the lecturer presented them. As you review cards that contain a concept and the surrounding concepts, you will be exposed to the concept in the context of the bigger picture through repeated interleaving. That is, in between cards on a particular concept the software will be showing you other cards that are often about related concepts.

As you see these interleaving, you’ll start to understand the similarities and differences between concepts. Once you can do this, you’ll be able to answer the cards quickly and with great accuracy.

Reviewing Cards

I review my cards every day. If you don’t they will build up. It takes me about an hour every day and I often split it up into two 30 minute sprints. Sometimes I find it convenient to review cards on my iPhone with the mobile app. Especially on a long bus ride. The desktop app is fine, but I use a plugin called Full Screen to maximize the window on my Mac to reduce distractions. Recently, I’ve started to stand while reviewing to limit my wandering mind.

Tony, while proofreading this post noted that he thinks I should attribute the better grades with Spaced Repetition to just studying more. He is probably correct. Spaced Repetition allows me to study effectively (not necessarily efficiently). I do spend a huge amount of time creating cards and reviewing them but the value I gain is immense.

Test Time

A great way to study for the kinds of exams I took in engineering is to practice problem sets or old exams. I find problems similar to or in the same style as those that will be on the exam. Before space repetition, each problem with a new concept required a haphazard search of lecture slides and my notes. Even once I had understood the concept and successfully completed the problem it was difficult to redo a similar problem later on during the exam study period. I couldn’t recall the specifics of the concept.

I found that because I had studied the concepts in the months leading up to the exam, the time I spend practice problems is efficiently used. When I did a problem, I had already learned the concept and its relationship with other concepts. Once I complete many of the practice problems, I’ll review the entire deck of cards for the course using the Filtered Decks feature. Filtered Decks allow me to refresh my memory on the entire course and to pinpoint areas that need concentration.

Conclusion

I urge students to consider alternative studying methods. It can be surprising what works for you. When you find a technique that works well for you it can change your whole attitude to exams and studying. The most valuable lesson I learned in university was how to learn.

##Acknowledgments

First I’d like to thank Derek Sivers of CD Baby fame introducing me to spaced repetition through this post. Second, the authors of SuperMemo for their excellent list on formulating knowledge. Third, my editor Tony Dong. Last, thanks to Damien Elmes for creating and maintaining Anki, the spaced repetition software I rely on.